Speculative Lands

Textile and sound Installation, 2024

Fabrics formerly used in and collected from farms and rural areas across Europe, threads, webbing, metal eyelets, agricultural blue twine, ring insulators.

Total size of the unfolded installation, around 90 m2.

Audio: Soundscape made up of different languages and durations.

Exhibition view of the solo show Speculative Lands, at Uus Rada Galleri, Tallinn, Estonia, 2024.

Uus Rada Gallerii, Tallinn, Estonia, 2024. Photography: Joosep Kivimäe

Speculative Lands is a textile installation consisting of eight separate works based on cadastral plans* of eight fields of my mother’s farmland in the South-East of France. They are made out of used fabrics collected from farms and rural areas. Together, they create a suspended textile architecture that invites the viewer to enter.

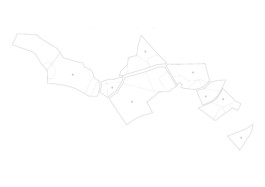

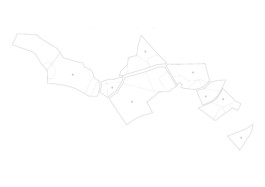

Montage of cadastral maps assembled with the eight fields of the family farm that make up the textile installation Speculative Lands

Cadastral plans of the fields I work with to create the shapes of the various textile elements that make up the tent structure.

Legend of Fields

The textile installation consists of 8 fields that make up Denise Gonon’s farmland. “The farm” is an entity com- prising the land, the agricultural and domestic build- ings on it as well as the activities related to them. The names of the fields are mostly vernacular names that exist as an oral tradition. They are rarely used in admin- istrative documents. At times, they use the name of an existing place, a path or a wood surrounding them. This generally gives an indication of where they are located. They may also pick up the name of a feature, an adjec- tive that qualifies what they look like, or describes what goes on above or below them. They are generally intended for those familiar with the area.

❶ malmonta (t)

[Malmontat is the name of a nearby small path. It could translate to “hard to climb”]

With or without a “t”, depending on the moment. Still my favorite spot for picnics, and the field where I used to take refuge, as a teenager, to dream of something else, far away from here. It offers a view over the plain, an immense horizon where you can see Mont du Pilat, Chalmazel and even, according to legend, Mont Blanc on a clear day.

❷ la ferme [the farm]

Everything is life and everything is work. There’s always something to do: tinkering, sewing, chopping wood, working in the fields, cooking, feeding the chicken and keeping all sorts of things, because “you never know, it might come in handy”. It’s a place with many entrances and exits. There’s always someone stopping by for a cup of filter coffee and grabbing a slice of yogurt cake.

❸ le grand pré

[the large meadow]

My mother’s favorite field, the one she sees from the house. If she didn’t see it every day, she’d miss it a lot. It’s cultivated differently depending on the season. The corn sometimes obstructs the view from the path, the wheat brings soothing movement and the cows graze peacefully. As she rightly says, agriculture shapes landscapes.

❹ le fondrier

[“frondrière” translates to crevices in the ground]

To prepare the field for summer silage, my father cut rows of standing corn the width of the tractor to create a passage. I used to drive the tractor with the small trailer and backed it gently into the newly created passage. It was difficult and technically demanding. I felt grown- up, useful, and wanted to be a boy.

❺ la terre du cimetière [the cemetery land]

As its name suggests, this field borders the small communal cemetery. Almost all my family members are buried here. I like to stop by to say hello to my aunt Janette and bring her flowers from the fields when I return to the village. I also remember the hunters setting crow traps there – a magnificent large cage that I hoped to find empty. Looking back, it made a beautiful sculpture.

❻ le grand chemin [the long way]

A field along a way that isn’t all that long after all. When the fields were ploughed, rocks came out of the ground. To avoid damaging the machines that would be used to sow the seeds, my siblings and I had to pick them up. We repeated this work every year, as if rocks were growing afresh every season. My father then used these rocks to fill in the paths made by the rain.

❼ le pré du cheval [the horse meadow]

I don’t remember ever seeing a horse on this meadow. At most, there’s a hut that bears witness to a past presence. There’s also a well from which my father used to draw water for the cattle. These were special opportunities to talk about life. I was a child and absorbed the worries of the farm while listening to songs of Tino Rossi, broadcasted by the tractor’s radio cassette.

❽ le bois du châtaignier [the chestnut wood]

A place to pick chestnuts in the fall together with my sister and my mother. They are cooked in water and eaten with cold whole milk straight from the milk tank. The small wood is really dense nowadays and the neighbors above have taken the opportunity to empty their trailer of stones in a hidden part. “Not seen, not caught”. But everyone knows.

"Legend of Fields" was conceived and written for the Speculative Lands exhibition in Tallinn, and featured on the exhibition flyers designed as an unfolding map. Graphic Design: Typokompanii (Andree Paat, Aimur Takk)

Speculative Lands

by Laura De Jaeger

for the exhibition at Uus Rada Gallerii, Tallinn, Estonia, April 2024

By this time of the year, my calendar moves on from the buienmaand, also referred to as the lentemaand, to the grasmaand. The old Germanic terminology of months is bound to the seasons. Each name softly fluctuates between its character and its consequences. March is when spring hits off (lente) which includes the necessary showers (buien). The outcome of those first rays of sun and the never-ending rainfall is that in April, the grass starts sprouting. The month of February however, carries the name of a human activity as a response to the present climate. Gleaning (sprokkelen) means to harvest what has been left on the fields.

The central material in the exhibition employs the practice of gleaning. For a year, Gisèle Gonon gathered a large number of used fabrics from European rural areas, above all Estonia and France. The pieces blend together as well as they carry distinctive traces of their past use. In a conceptually consistent manner, the artist sutures them together with material that is intrinsically connected to farming processes. Guided by cadastral maps of her mother’s farmland in the French rural region of Monts du Lyonnais, she opens up questions about tenure, appropriation, and exploitation of space.

Speculative Lands uses labour as a peculiar yet successful tool to resonate on a personal as well as collective level. I find a similar approach in the writing of Annie Ernaux, painting a sensitive portrait of her father in A Man’s Place. It is through describing his relation to work that we can truly see him as a person. As can I see my own father, a mechanic, through her narrative. In The Gleaners and I, Agnes Varda interviewed practitioners throughout rural and urban France. Her insistence on the personal narratives of each group managed to coin the notion of gleaning at large. The filmmaker’s starting point was an oil painting from 1857 by Jean-François Millet named Des glaneuses. Unlike Ernaux’ example, the movie’s original French title (Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse), as well as the painting’s subject are women. In Uus Rada, Gonon consciously focuses on the female lineage of her family in the framework of labour as well as ownership.

Millet’s painting caused controversy with its unconventional portrayal of the working class, glorifying the practice on farmlands at an immense scale. Gisèle Gonon creates her own leeway in the hard matter of data by elevating flat matter to a cave-like structure and inviting the visitor in. When land becomes a shelter, it can provide an escape route for ownership not to fall into traps of economically-driven power structures such as land grabbing. Instead, it becomes a setting and designated space for a multitude of narratives. Invitation replaces appropriation. We can see this in the use of material, combining fabrics from diverse contexts. But the patched land also houses distinct whispers, each relating to fields, land, as well as the forest-like environment of the gallery space by means of their own mother tongue.

The exhibition takes place at the edge of the city. It’s rather symbolic to address farming, labour, and production at its original place – on the fringe, slightly outside. Yet this is a building for sculptural practices. Most of the public monuments in Tallinn were produced at Raja street and later transported to the central areas. During Soviet times, artists were often assigned the highest floor in the buildings in Lasnamäe, providing an incredible view, like the one a farmer has of their fields. Still, both are kept at distance while in continuous dialog and exchange with their surroundings. Gonon pinpoints a resemblance between artistic practice and farming labour – not only through the practice of gleaning but also a conscious investigative position towards time, repetition, and material. Whereas the building is equipped with a monumental studio for stone or plaster, and wood-, welding-, and plastic rooms, the artist invites soft, flexible material in the gallery space, as a fluctuating proposal that opens up space for rethinking commons and exchange.

Laura De Jaeger, March 2024

Estonian version of the text: https://giselegonon.net/speculative-lands-exhibition-text-2024-estonian/

Co-producer: Laura De Jaeger

Graphic Design: Typokompanii (Andree Paat, Aimur Takk)

Photography: Joosep Kivimäe

The artist warmly thanks Denise Gonon, Mara Kirchberg, Laura De Jaeger, Cathy Douvre, Marion Orfila, Ats Kruusing, Sandra Ernits, Solveig Lill, Sarah Noonan, everyone who took part in the fabric harvesting, the Estonian Academy of Arts, EKKM and Uus Rada.

The exhibition is supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia and the Stiftung Kunstfond.

Uus Rada is a community artist-run space located in a building designated to sculpture in Raja street, Tallinn, Estonia

Title: Speculative Lands

Open: 10.04.-20.04.2024

Uus Rada gallery, Raja 11a, Tallinn.

Tuesday – Sunday 14:00 – 18:00 or by appointment

Sound and HD pictures on demand.

Speculative Lands, Gisèle Gonon, 2024.

Textile and sound Installation, 2024

Fabrics formerly used in and collected from farms and rural areas across Europe, threads, webbing, metal eyelets, agricultural blue twine, ring insulators.

Total size of the unfolded installation, around 90 m2.

Audio: Soundscape made up of different languages and durations.

Exhibition views, Uus Rada Gallerii, Tallinn, 2024.

Photo: Joosep Kivimäe

Speculative Lands

Textile and sound Installation, 2024

Fabrics formerly used in and collected from farms and rural areas across Europe, threads, webbing, metal eyelets, agricultural blue twine, ring insulators.

Total size of the unfolded installation, around 90 m2.

Audio: Soundscape made up of different languages and durations.

Exhibition view of the solo show Speculative Lands, at Uus Rada Galleri, Tallinn, Estonia, 2024.

Uus Rada Gallerii, Tallinn, Estonia, 2024. Photography: Joosep Kivimäe

Speculative Lands is a textile installation consisting of eight separate works based on cadastral plans* of eight fields of my mother’s farmland in the South-East of France. They are made out of used fabrics collected from farms and rural areas. Together, they create a suspended textile architecture that invites the viewer to enter.

Montage of cadastral maps assembled with the eight fields of the family farm that make up the textile installation Speculative Lands

Cadastral plans of the fields I work with to create the shapes of the various textile elements that make up the tent structure.

Legend of Fields

The textile installation consists of 8 fields that make up Denise Gonon’s farmland. “The farm” is an entity com- prising the land, the agricultural and domestic build- ings on it as well as the activities related to them. The names of the fields are mostly vernacular names that exist as an oral tradition. They are rarely used in admin- istrative documents. At times, they use the name of an existing place, a path or a wood surrounding them. This generally gives an indication of where they are located. They may also pick up the name of a feature, an adjec- tive that qualifies what they look like, or describes what goes on above or below them. They are generally intended for those familiar with the area.

❶ malmonta (t)

[Malmontat is the name of a nearby small path. It could translate to “hard to climb”]

With or without a “t”, depending on the moment. Still my favorite spot for picnics, and the field where I used to take refuge, as a teenager, to dream of something else, far away from here. It offers a view over the plain, an immense horizon where you can see Mont du Pilat, Chalmazel and even, according to legend, Mont Blanc on a clear day.

❷ la ferme [the farm]

Everything is life and everything is work. There’s always something to do: tinkering, sewing, chopping wood, working in the fields, cooking, feeding the chicken and keeping all sorts of things, because “you never know, it might come in handy”. It’s a place with many entrances and exits. There’s always someone stopping by for a cup of filter coffee and grabbing a slice of yogurt cake.

❸ le grand pré

[the large meadow]

My mother’s favorite field, the one she sees from the house. If she didn’t see it every day, she’d miss it a lot. It’s cultivated differently depending on the season. The corn sometimes obstructs the view from the path, the wheat brings soothing movement and the cows graze peacefully. As she rightly says, agriculture shapes landscapes.

❹ le fondrier

[“frondrière” translates to crevices in the ground]

To prepare the field for summer silage, my father cut rows of standing corn the width of the tractor to create a passage. I used to drive the tractor with the small trailer and backed it gently into the newly created passage. It was difficult and technically demanding. I felt grown- up, useful, and wanted to be a boy.

❺ la terre du cimetière [the cemetery land]

As its name suggests, this field borders the small communal cemetery. Almost all my family members are buried here. I like to stop by to say hello to my aunt Janette and bring her flowers from the fields when I return to the village. I also remember the hunters setting crow traps there – a magnificent large cage that I hoped to find empty. Looking back, it made a beautiful sculpture.

❻ le grand chemin [the long way]

A field along a way that isn’t all that long after all. When the fields were ploughed, rocks came out of the ground. To avoid damaging the machines that would be used to sow the seeds, my siblings and I had to pick them up. We repeated this work every year, as if rocks were growing afresh every season. My father then used these rocks to fill in the paths made by the rain.

❼ le pré du cheval [the horse meadow]

I don’t remember ever seeing a horse on this meadow. At most, there’s a hut that bears witness to a past presence. There’s also a well from which my father used to draw water for the cattle. These were special opportunities to talk about life. I was a child and absorbed the worries of the farm while listening to songs of Tino Rossi, broadcasted by the tractor’s radio cassette.

❽ le bois du châtaignier [the chestnut wood]

A place to pick chestnuts in the fall together with my sister and my mother. They are cooked in water and eaten with cold whole milk straight from the milk tank. The small wood is really dense nowadays and the neighbors above have taken the opportunity to empty their trailer of stones in a hidden part. “Not seen, not caught”. But everyone knows.

"Legend of Fields" was conceived and written for the Speculative Lands exhibition in Tallinn, and featured on the exhibition flyers designed as an unfolding map. Graphic Design: Typokompanii (Andree Paat, Aimur Takk)

Speculative Lands

by Laura De Jaeger

for the exhibition at Uus Rada Gallerii, Tallinn, Estonia, April 2024

By this time of the year, my calendar moves on from the buienmaand, also referred to as the lentemaand, to the grasmaand. The old Germanic terminology of months is bound to the seasons. Each name softly fluctuates between its character and its consequences. March is when spring hits off (lente) which includes the necessary showers (buien). The outcome of those first rays of sun and the never-ending rainfall is that in April, the grass starts sprouting. The month of February however, carries the name of a human activity as a response to the present climate. Gleaning (sprokkelen) means to harvest what has been left on the fields.

The central material in the exhibition employs the practice of gleaning. For a year, Gisèle Gonon gathered a large number of used fabrics from European rural areas, above all Estonia and France. The pieces blend together as well as they carry distinctive traces of their past use. In a conceptually consistent manner, the artist sutures them together with material that is intrinsically connected to farming processes. Guided by cadastral maps of her mother’s farmland in the French rural region of Monts du Lyonnais, she opens up questions about tenure, appropriation, and exploitation of space.

Speculative Lands uses labour as a peculiar yet successful tool to resonate on a personal as well as collective level. I find a similar approach in the writing of Annie Ernaux, painting a sensitive portrait of her father in A Man’s Place. It is through describing his relation to work that we can truly see him as a person. As can I see my own father, a mechanic, through her narrative. In The Gleaners and I, Agnes Varda interviewed practitioners throughout rural and urban France. Her insistence on the personal narratives of each group managed to coin the notion of gleaning at large. The filmmaker’s starting point was an oil painting from 1857 by Jean-François Millet named Des glaneuses. Unlike Ernaux’ example, the movie’s original French title (Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse), as well as the painting’s subject are women. In Uus Rada, Gonon consciously focuses on the female lineage of her family in the framework of labour as well as ownership.

Millet’s painting caused controversy with its unconventional portrayal of the working class, glorifying the practice on farmlands at an immense scale. Gisèle Gonon creates her own leeway in the hard matter of data by elevating flat matter to a cave-like structure and inviting the visitor in. When land becomes a shelter, it can provide an escape route for ownership not to fall into traps of economically-driven power structures such as land grabbing. Instead, it becomes a setting and designated space for a multitude of narratives. Invitation replaces appropriation. We can see this in the use of material, combining fabrics from diverse contexts. But the patched land also houses distinct whispers, each relating to fields, land, as well as the forest-like environment of the gallery space by means of their own mother tongue.

The exhibition takes place at the edge of the city. It’s rather symbolic to address farming, labour, and production at its original place – on the fringe, slightly outside. Yet this is a building for sculptural practices. Most of the public monuments in Tallinn were produced at Raja street and later transported to the central areas. During Soviet times, artists were often assigned the highest floor in the buildings in Lasnamäe, providing an incredible view, like the one a farmer has of their fields. Still, both are kept at distance while in continuous dialog and exchange with their surroundings. Gonon pinpoints a resemblance between artistic practice and farming labour – not only through the practice of gleaning but also a conscious investigative position towards time, repetition, and material. Whereas the building is equipped with a monumental studio for stone or plaster, and wood-, welding-, and plastic rooms, the artist invites soft, flexible material in the gallery space, as a fluctuating proposal that opens up space for rethinking commons and exchange.

Laura De Jaeger, March 2024

Estonian version of the text: https://giselegonon.net/speculative-lands-exhibition-text-2024-estonian/

Co-producer: Laura De Jaeger

Graphic Design: Typokompanii (Andree Paat, Aimur Takk)

Photography: Joosep Kivimäe

The artist warmly thanks Denise Gonon, Mara Kirchberg, Laura De Jaeger, Cathy Douvre, Marion Orfila, Ats Kruusing, Sandra Ernits, Solveig Lill, Sarah Noonan, everyone who took part in the fabric harvesting, the Estonian Academy of Arts, EKKM and Uus Rada.

The exhibition is supported by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia and the Stiftung Kunstfond.

Uus Rada is a community artist-run space located in a building designated to sculpture in Raja street, Tallinn, Estonia

Title: Speculative Lands

Open: 10.04.-20.04.2024

Uus Rada gallery, Raja 11a, Tallinn.

Tuesday – Sunday 14:00 – 18:00 or by appointment

Sound and HD pictures on demand.

Speculative Lands, Gisèle Gonon, 2024.

Textile and sound Installation, 2024

Fabrics formerly used in and collected from farms and rural areas across Europe, threads, webbing, metal eyelets, agricultural blue twine, ring insulators.

Total size of the unfolded installation, around 90 m2.

Audio: Soundscape made up of different languages and durations.

Exhibition views, Uus Rada Gallerii, Tallinn, 2024.

Photo: Joosep Kivimäe